Eva Slater: The Death Valley Journey of a Modern Artist

Life in the Slater household in 1950s Orange County was like living in a mid-century modern postcard. John and Eva Slater and their kids, Dan and Miriam, lived in a custom-built A-frame house aligned with the North Star.

John Slater worked as an inventor and chief scientist at Autonetics—what could be more Space Age? Eva Slater, born in Berlin, Germany, in 1922, was part of an uber-cool modern art movement called Hard Edge.

She and her artist friend Helen Lundeberg were both inspired by the geometry of the desert; both made trips to Death Valley and Palm Springs. Yet, only one of these artists went on to become famous.

“Everyone knows Helen Lundeberg. No ones knows my mom. She just walked away,” says Slater’s daughter Miriam, also an artist in Santa Barbara.

Why did Eva Slater leave the postcard life? Where did she go?

Today, Eva Slater is 88 and in poor health. She lives with her daughter, Miriam, who wants people to know her mother’s work and to recognize her forgotten place in California art. Hers is a story that leads deep into the California desert.

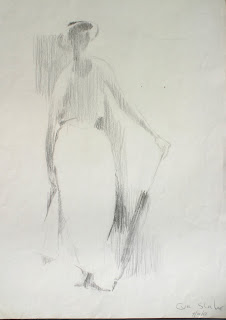

Eva Slater moved to the US from Berlin after the war and worked as a fashion illustrator in New York City. Later, while studying at the Art Center College of Design in LA, she met artists Frederick Hammersley, Helen Lundeberg and her husband, Lorser Feitelson, the acknowledged founder of Hard Edge. The painters frequently dropped in at the Slater household, adding even more style to the family’s stylish lives.

For a break from the city, the Slaters sometimes went on car trips to the desert: Utah, Arizona, Death Valley and Palm Springs. John would snap photos that Eva would later transform into abstract paintings. John himself painted traditional desert landscapes.

“The desert suited her (Eva’s) personality,” says Miriam. “She really liked the big space.”

In the Hard Edge world, landscapes were drawn from imagination rather than directly from nature. In Slater’s “Desert Rain”, for example, the painter started with John’s photo of a rainstorm and turned it into a sketch of only a few lines. Then it morphed again into a painting showing an abstract curtain of rain sweeping geometric buttes.

As Helen Lundeberg once said of a 1971 landscape painting: “It doesn’t represent anything any one ever saw on God’s earth or in the sky.”

Miriam Slater explains that Hard Edge is dependent on “rhythm, counterpoint, playing off opposites—that’s how you generate excitement.” She says the paintings were constructed with a lot of thought, describing a process almost like architecture.

The innovation was one of the first true LA exports to the modern art world, according to critic Benjamin Schwarz. He wrote in The Atlantic: “Southern California produced little noteworthy modern art before the austere, crisply defined Hard-Edge geometric paintings.”

So there was Eva Slater in the 1960s, exploring shapes and landscape, mixing at art world parties and enjoying the fruits of an OC high tech lifestyle. It all sounded pretty good. Why then did she change direction so completely? “We all kind of wondered,” Miriam says.

In the mid-1980s Eva Slater strolled into the Eastern California Museum in Independence, a little town tucked between the Sierras and Death Valley. She was there to inquire about local Indian basketmakers.

“She was wandering around the desert alone in an old vehicle,” says Bill Michael, then director of the museum. “Sometimes her husband would come along but she’d park him in a motel in Lone Pine. For years, all we talked about was baskets.”

Slater began researching a book she planned to write on the local basketmakers. Spending more and more time in Death Valley, she befriended Indians and sought the abandoned camps of the early artists. She was often alone but sometimes accompanied by her husband, John, daughter Miriam and Miriam’s husband Harry Carmean, also an artist who had been a student of Loser Feitelson.

“We would travel through the Panamint mountains, through the Saline Valley, and hike into desolate areas,“ says Miriam. Eva Slater frequented Darwin Wash, Hunter Canyon and the canyons above Lone Pine, searching for the basketmakers’ materials in their natural settings–willow, yucca root, devil’s claw, porcupine quill and woodpecker feathers. She’d walk for miles to find a rare junca that turned golden at a certain time of year.

In her former life, it sometimes took Slater a year to make a single painting; it took her ten to research and write her book: Panamint Shoshone Basketry: An American Art Form. “Her devotion to her chosen subject has never waned, wavered or abated,” wrote Armand Labbe of the Bowers Museum, in the introduction.

In the book jacket photo, Slater’s appearance contrasts with her sleekly modern look in the family’s early photos. Now past middle-age and suffering from heart problems, Slater has tousled graying hair and wears a faded, buttoned-up work shirt. To fellow travelers in Death Valley, she must have seemed to be yet another eccentric anthropologist out to plumb the secrets of the dunes.

Jane Wehrey, who met Slater in the early 1990s when the artist appraised her basket collection, says of her: “The word ‘patrician’ comes to mind. She was a lady; it was very apparent.”

To Wehrey, too, Slater talked little about her life in art. “I remember her saying something like: ‘That was another time. I’m done with that.’”

As Slater’s life became more entwined with the Shoshone Indians, she enlisted a builder to make her a house in Lone Pine. Her city house had been aligned with the North Star; this house would be aimed at Mount Whitney. The interior would be one large loft-like room lined with 15-foot display cases for her baskets. In concept, it was a museum. “It was a house secondarily,” says Wehrey.

The builder, Francis Pedneau, was accustomed to demanding clients from the city, but Slater kept him jumping. First she wanted all the exposed nuts and bolts on the trusses painted one color. Then the color wouldn’t do at all and Pedneau had to start again.

Pedneau also talked baskets with Slater, and says she was fascinated by the utilitarian aspect of basket art. In LA, people made paintings to be seen and talked about. In the desert, he says, “they made baskets because they needed them.

Slater’s husband, John, had died by the time Slater moved her baskets into the Lone Pine house. She never had a chance to completely move in herself. Worsening heart problems forced her to give up her plan to move to the eastern Sierra. In 2001, she donated much of her basket collection to the Eastern California Museum.

Then-director Bill Michael had only known her as a basket fanatic, but now he had an opportunity to visit her home in LA. It was then, when he saw the paintings on the wall, that he began to realize Slater had a former glamorous life—one she never talked about.

The Lone Pine house sat empty for six years until one day in 1998. Maggie Wittenburg, then a producer for CBS News, was driving up Highway 395 for a needed getaway on the anniversary of a friend’s death. On impulse she stopped to look at the property.

It was peculiar from the street–the front of the house looked like the back. But when she looked in the windows she knew she was home: “Oh my God, somebody built my dream house.” Wittenburg left her life in LA and moved into Slater’s dream house, where she lives to this day. “It’s just the best place in the world,” she says.

Helen Lundeberg and Lorser Feitelson, both deceased, are again the talk of hip art circles. Hard Edge is coming back into vogue, especially in Europe. The Orange County Museum of Art launched a 2002 show that featured Hard Edge: “The Birth of the Cool”. The rock group Sonic Youth wrote a song honoring Lundeberg, a sure sign of having arrived in modern culture.

In contrast, there have been no songs written for Eva Slater. The house in Lone Pine still draws gawkers, but only because it’s unusual and not because the artist lived there. You have to search hard to find Slater’s paintings.

For now, the lasting testament to Slater’s life and career is her basketry book. It remains a classic because its one of the few to approach basketry as art, not strictly anthropology.

At first glance, Slater’s two lives appear to have no connection. But studying the baskets and paintings, you start to see the cord. The basketmakers began with the raw material of the land—the shapes of buttes and snakes. That was only for starters. Their essential job was to mix in emotion and imagination, to create something that was more than utilitarian.

Slater, too, began with a desert rainstorm and added a personal ingredient that helped make Hard Edge an international sensation.

When Slater describes the job of a basketmaker–“Composing and adjusting the rhythm, play of form, line, color and texture to express a human experience”–it sounds exactly like the task of a Hard Edge artist.